For the past few months, I’ve been putting together a pamphlet of advice and collected wisdom for students just graduating from architecture school. The pamphlet will be released online as a free PDF next month. If you want to support this project, please read more and consider donating a few bucks here. (All money goes to contributors for their writing or for the direct logistical costs of distribution.)

In the next few weeks I’ll be sharing some excerpts and behind-the-scenes research from putting the pamphlet together. This post, on the confusion of job titles for recent graduates, is the first of these little previews.

What exactly should your job title be as a recent graduate?

Suppose you’re about to graduate from architecture school and you’re looking for jobs. You might log into Indeed or ZipRecruiter and search for open positions in your area.

Maybe you’ve been on the job for two years now, making progress toward licensure, and want to ask for a raise. You want to be well-prepared and a good advocate for your own value, so you try to look up what other people in similar positions make.

Or perhaps you’re in a more senior role, trying to hire someone who fits the descriptions above. The job postings you’ve been placing aren’t bringing in that many candidates, and you’re wondering if something in the job description is pushing people away.

Naturally, in any of these situations you’ll need to find a clear term to describe the type of position you’re thinking about: a job for someone with a degree in architecture but no license, with 0-3 years of experience, employed in an architecture office, and working on drawings, models, and renderings. What job title(s) are you looking at when doing your research?

In the past, the word “intern” (as in “Intern Architect” or “Architectural Intern”) has been used to refer to both the position described above and for students working in an architecture office while completing their degrees. In late 2016, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) recommended a move away from the “intern” language to describe recent graduates, suggesting instead “architectural associate” or “design professional.”

Alas, these terms only seem to muddy the waters further. A blog post from the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) in 2017 explains:

“In 46 U.S. jurisdictions, the use of the term "architectural associate" is prohibited, and in 26 jurisdictions, the term "design professional" may be an issue. In addition, 23 states define an "intern" as a post-graduate employee within their law—meaning that candidates cannot describe themselves as an intern prior to graduation.”

Because licensing boards operating at the state level set their own regulations, there’s no one standard, nationwide definition of what any of these terms mean or when it’s okay to use them. A title that’s permitted or even recommended on the east coast may be illegal in California.

Now, there’s a moral and ethical difference between mistakenly using a term you sincerely believed to be correct and deliberately falsifying qualifications or forging documents. All the same, I strongly recommend looking up the rules in your jurisdiction and proceeding accordingly. NCARB maintains a list of licensing boards and their contact info here.

How do professional data-gatherers answer the question?

So that’s the legal side of things, as far as I can tell. But even if you’ve settled on a legally appropriate job title, how do you evaluate it against other comparable positions?

The AIA publishes regular compensation reports, derived from surveys of architecture firms nationwide. In the 2021 Compensation Report, the category that best fits the description of these types of roles is:

RECENT COLLEGE GRADUATE (NON-LICENSED)

(o-3 years’ experience) Non-licensed architectural staff.

Professional degree in architecture. Full-time, entry-level professional performing basic architectural assignments. Undertakes a variety of assignments requiring the application of standard architectural techniques for small projects or selected segments of a larger project. Performs design layouts and features, which require researching, compiling, and recording information for assigned project work.

In the report prepared specifically for small firms, however, the job titles are defined differently. The closest corresponding category for our interests is described as follows:

“An emerging architectural professional is a design professional on the path to licensure.”

I believe the different terminology for small firms is primarily a function of how the surveys are built and the overall sample size of the data. That probably makes sense from a perspective of statistical accuracy, but it also muddies the waters for understanding job titles and comparing compensation. After all, making models and populating renderings isn’t a fundamentally different job in a 3-person office or a 300-person office: the same skillsets and education are required for both and plenty of people will experience multiple firm sizes over the course of their careers.

Setting the AIA nomenclature aside, if you were to purchase market research reports prepared by third-party entities like Zweig Group or Pearl Meyer, you’d see terms like Architect (Intern), Architect (Project Coordinator), or Architectural Junior Designer ‘A,’ each with definitions similar (but not identical) to the categories above.

On the publicly-funded research side of things, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (an otherwise incredibly useful resource for all workers) does not, unfortunately, break its wage data down beyond a distinction between Architects and Drafters.

All of which is to say that the world of market research and professionally-calculated earnings statistics has just as much ambiguity as the law itself. If you, like me, are trying to gather a bunch of estimates for roughly the same job in different parts of the country, the fuzzy terminology makes it hard to tell if you’re even comparing apples to apples most of the time.

What do workers reporting their own titles say?

A third way to gather info about job titles is via self-reported data. This has advantages and disadvantages.

On the positive side, there’s a chance of seeing info not usually available in other places. Firms that pay rock-bottom salaries are, one imagines, less likely to disclose this information to the AIA. That goes double for firms that rely on unpaid interns or other payscales of questionable legality. It’s hard to get an accurate number of how many there are, but we all know these offices exist and employ people. And those people are perfectly free to report their own hours, pay, and working conditions to others.

The best resource I’ve come across for this sort of information is the anonymous salary poll run by Archinect. If you’re not already familiar with this tool, please stop reading, click the link in the previous sentence, and add your own salary information to the database. At the time of writing, there are over 16,000 salaries recorded, along with information about education, experience, location, benefits, and more. The tool makes it easy to sort and filter across all of these different categories and, assuming others in your region have input their own salaries, you can get a decent snapshot of what pay ranges look like for someone in your situation.

I mentioned a minute ago that there are some disadvantages here, too. There’s no way to know if the anonymous data is truly “representative” of a particular demographic or region, or if it’s skewed by a high (or low) number of responses from a particular firm or cohort. Also, as far as I can tell the Archinect data is not monitored or cleaned up: when looking I came across occasional quirks that I think must be simple mistakes, like a reported salary of $54 per year, where the intended figure was presumably $54,000. But any salary estimate will always be just that—an estimate. And with a few filters on the data, we can get some usable information.

The data in the chart below was gathered by filtering for six particular job titles: Designer, Junior Architect, Intern, Junior Designer, Associate, and Draftsperson. I also constrained results to 0-3 years of experience, only included positions in the United States, and set the “floor” of the data to $15,500/year to remove any reported salaries below the federal minimum wage. From the 2461 results that came up, more than half of respondents described their title as Designer or Junior Architect. The reports self-describing as an Associate or a Draftsperson made up about 7% of the filtered responses, and Intern and Junior Designer filled out the remainder. Within this set of salaries, three-quarters were grouped around $50,000 per year, with the rest coming in closer to $41,000.

DISTRIBUTION OF SELF-REPORTED JOB TITLES AND AVERAGE (MEAN) WAGES BY TITLE

I didn’t do this myself, but an interesting exercise might be to map the geographic location of these titles, particularly in light of the varying legal landscape listed above. Does calling yourself an Intern reduce your wages, or are Intern titles just the preferred nomenclature in areas that have lower wages generally? Hard to say, but it sure would be good to know!

And how about those big job search sites?

One last place I checked in preparing this was the “Salaries” tab on some of the big job search sites. Monster, sort of like the Bureau of Labor Statistics, lumps everything into either Architect or Civil / Architectural Designer / Drafter. Not terribly helpful for this inquiry. But both Indeed and ZipRecruiter have some more fine-grained distinctions. I was also curious about the geographic distributions I hinted at above, so I looked at those a little bit too.

Unlike the solely-professionally-gathered or the solely-self-reported data, the job search sites seem to aggregate a bit of both. At least, as far as I can tell. They don’t disclose the full methodology behind their salary estimates, but generally they draw from employer-posted job ads, employee-submitted salaries, and various other sources, including large payroll-management enterprises. So it’s a bit of a mixed bag.

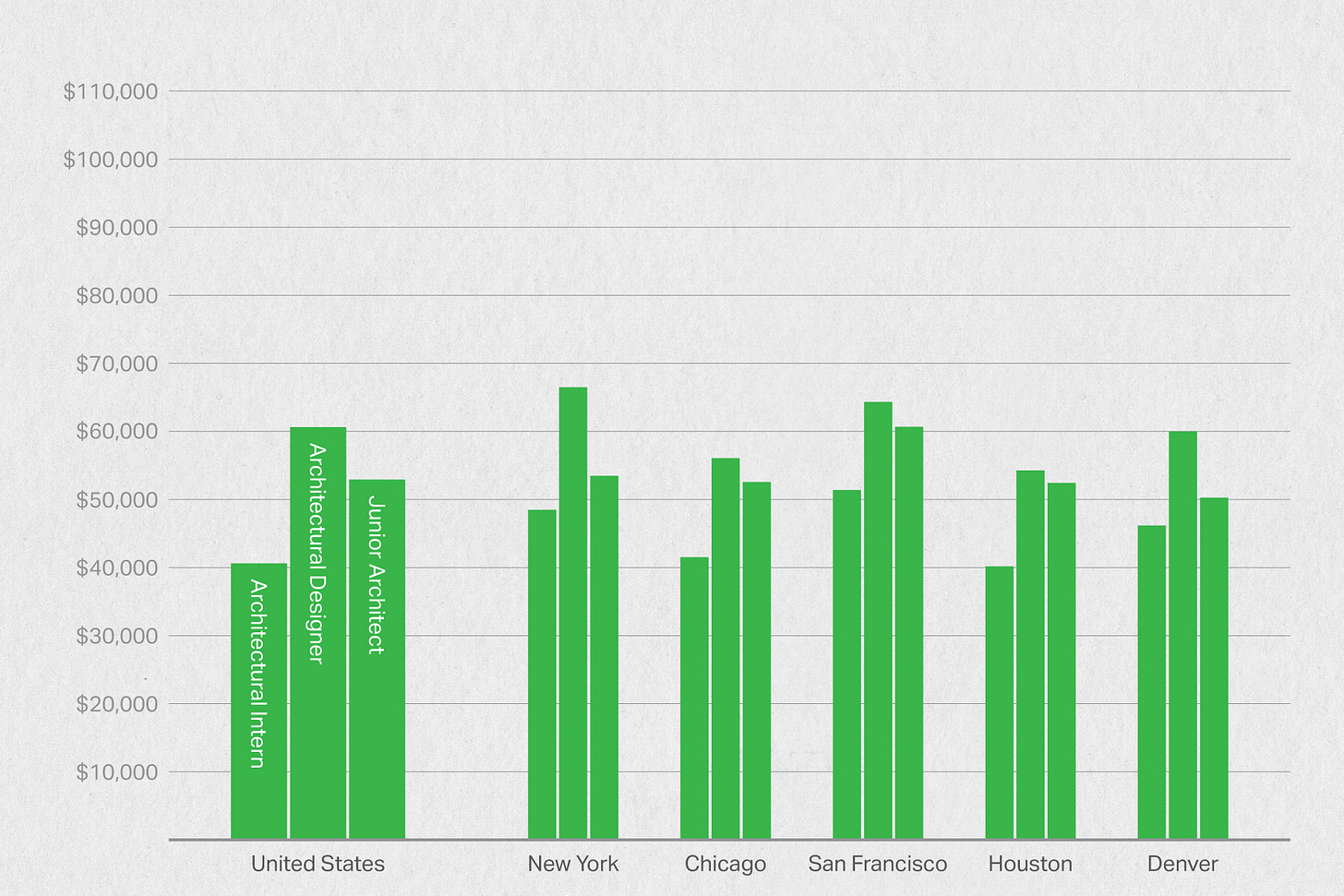

Both Indeed and ZipRecruiter had data available for Architectural Interns, Architectural Designers, and Junior Architects. I pulled the numbers for all three titles both at the U.S.-wide level and in five particular cities: New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Houston, and Denver. These choices were fairly arbitrary, but they gave some interesting results, as can be seen in the charts below.

AVERAGE (MEAN) WAGES BY TITLE AND LOCATION, INDEED

AVERAGE (MEAN) WAGES BY TITLE AND LOCATION, ZIPRECRUITER

I don’t have a good answer for the Junior Architect salaries jumping so much in San Francisco and Houston in the Indeed data. In general, the Indeed figures jump around a bit compared to the ZipRecruiter, which is a bit more consistent.

With both the Archinect poll results and the job search data, the Intern positions come in lower than other titles. My hunch is that these figures include some positions held by students still working on their degrees, but ultimately, it’s just that—a hunch.

The Advice Part

So: as a recent graduate, what job title best describes the work you do?

I would love to have a simple, one-size-fits-all answer to this, but I don’t. The legal and practical landscape is just too fragmented to point to one particular title that will be both legally appropriate and commonplace in the job market for all locations. This fact feels like the sort of low-hanging fruit that our various professional organizations ought to be able to solve, but I gather that there are quite a bit of complicated internal relationships and disputes at work preventing any clear progress, at least in the short term.

So, in lieu of any one particular term, I’m offering a few general guidelines for how you describe your role to other people and how you go about salary research.

Prioritize clarity and honesty

Never ever (ever!) claim to be a licensed architect until you are, in fact, licensed. That’s a term with a specific meaning and serious consequences for misuse. We’ve all, uh, “put ourselves in the best light” on a resume from time to time. The job title is not a place to stretch anything. I would probably avoid Intern Architect or Junior Architect for this reason, but (as the data above shows) there are plenty of contexts where these titles are commonplace.

Consider your audience

The term Architectural Designer will probably be understood differently by a hiring manager for a large firm than it would be by your grandmother or by a stranger at the bar. This isn’t a value judgment, nor is it a reason to chime in with a condescending “Well, actually…” to someone you’ve just met in passing. But if anyone is trying to pay you for architectural work or solicit advice about an architectural project, you should be very, very clear about your qualifications and experience.

Research your context

The terms most commonly used on resumes and job postings in Sacramento might be different from those used most in Boston. If you’re applying to a job in a new city or trying to estimate salaries in an area you don’t know extremely well, it’s probably worth searching half a dozen terms, just to be sure you’re being presented with the most accurate information. It would be a shame to be qualified and competitive at a $55,000 level but only paid $40,000 simply for using the “wrong” term when job hunting. A good and conscientious employer wouldn’t let this happen, but not every employer fits that description. And, as mentioned earlier, I highly recommend checking in to what your local state board mandates. The best time to stop a messy legal issue is before it happens.

And, as a final note: I am a well-intentioned stranger on the internet, not a lawyer or statistician or representative of any accrediting body. I’ve done my best to ensure that all of the above is accurate, but I can’t make any promises that it’s fully and 100% correct. It’s my strongest hope, however, that it’s helpful and informative.

In warm love and solidarity,

THA